Ashley K. Yeh1,2*, Britney O. Pennington1,

Mohamed A. Faynus1,3, Mika Katsura1, Dennis O.Clegg1,4,5

1 Center for Stem Cell Biology and Engineering, Neuroscience Research Institute, University of California, Santa Barbara, 93106, CA

2 College of Creative Studies, Chemistry and Biochemistry, University of California, Santa Barbara, 93106, CA

3 Program for Biomolecular Science and Engineering, University of California, Santa Barbara, 93106, CA

4 Program in Biological Engineering, University of California, Santa Barbara, 93106

5 Department of Molecular, Cellular, and Developmental Biology, University of California, Santa Barbara, 93106, CA

Abstract

Vision impairments affect over 2.2 billion people worldwide. The most physiologically accurate human retina models are Retinal Organoids (ROs) — stem cell-derived structures containing the major cell types found in the human retina. However, the current protocol for deriving ROs from stem cells is highly labor-intensive and involves a time-consuming neural induction period. In this study, we investigated an alternative differentiation protocol that could decrease the neural induction period from two weeks to four days and elucidate the essential parameters, such as seeding density, required for neural induction of ROs. Expediting the neural induction of RO progenitors can be applied to improve efficiency in the differentiation of ROs.

We characterized RO progenitors using gene expression data from qPCR and by visual inspection with bright-field microscopy. Although seeding density has historically been shown to affect gene expression in the culture of ocular cells, seeding density did not significantly (p > .05) impact the gene expression or morphology of cells at the tested time points of differentiation. Cells on day 4 (D4) of differentiation demonstrated morphology and neural gene expression (Pax6 and Lhx2) characteristic of neural cells. Additionally, transferring cells from adherent culture to suspension culture on day 2 (D2) instead of D4 of this differentiation yielded intact neural spheres with a phase-bright outer ring and defined borders after 14 days of culture. Therefore, these results indicate that our alternative differentiation protocol successfully expedited the neural induction of RO progenitors. These results will contribute to the establishment of a more efficient neural induction when generating ROs, which may expedite the production of RO-based retinal therapies.

Introduction

Among the most common visual impairments are age-related macular degeneration (AMD), glaucoma and diabetic retinopathy, all of which are incurable degenerative eye diseases collectively responsible for over 400 million cases of impaired vision (World Health Organization 2021). This number is projected to double by 2050, which could have considerable financial and medical implications for the future (Zheng et al. 2012; Wong et al. 2014; Allison et al. 2020). To keep up with the increasing need for efficient and effective therapies for these diseases, scientists require an accurate model of the human eye that can recapitulate the morphology and physiology of the retina in vivo.

Historically, studies investigating the causes and mechanisms behind retinal disorders have used 2D cultures of select retinal cell types, explants of certain regions of the retina and animal models (Chen et al. 2017; Armento et al. 2021; Petters et al. 1997). Though useful in many cases, animal models and 2D cultures fail to reproduce specific processes native to the human retina (Schnichels et al. 2021), such as the development and migration of retinal progenitors or synapse formation. Thus, a 3D model that can accurately replicate developmental milestones in the human retina is needed to model retinal disease and develop therapies efficiently.

A recently characterized system that mimics both developmental and physiological components of the human retina is Retinal Organoids (ROs) (Zhang et al. 2021). ROs are stem cell-derived structures that mature and contain the major cell types of the retina, including amacrine, ganglion, photoreceptor and bipolar cells. During RO maturation, retinal progenitor pools migrate under the guidance of signaling systems akin to in-vivo development and self-organize into the distinct cell layers observed in the human retina (Zhang et al. 2021). This makes ROs an effective tool for disease modeling and drug screening. To date, several studies have used ROs to model and provide valuable insights on multiple retinal diseases such as Retinitis Pigmentosa, Leber Congenital Amaurosis (LCA), Cone-rod dystrophy, AMD, Glaucoma and Diabetic Retinopathy (Diakatou et al. 2021; Kruczek et al. 2021; Zhang et al. 2020; Bird 2020; Aasen and Vergara 2020).

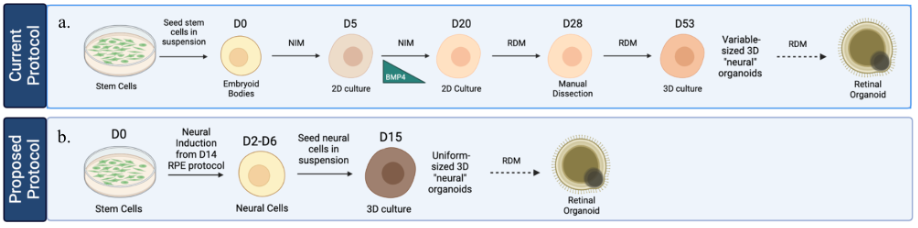

One notable obstacle hindering the widespread use of ROs is the lengthy and labor-intensive differentiation process. The current culture paradigms can take up to 250 days and involve several labor-intensive steps. Initially, stem cells are grown in suspension, forming embryoid body-like structures and pushed towards a neural fate, after which plating and long-term (one month) differentiation towards neural retina commences. Neural retina are manually dissected from adherent cultures, which allows for the natural transition towards fully formed ROs (Figure 1a). Traditional manual dissection introduces variability in experiments because it creates organoids of varying shapes and sizes while also increasing the potential for human error. The early stages, from neural induction to manual dissection of this differentiation protocol, may be optimized to improve efficiency and reduce variability.

Figure 1. Schematic of proposed protocol to expedite current RO differentiation protocol. a) Schematic of current RO differentiation protocol involving a 20-day neural induction period and manual dissection of 2D embryoid bodies on D28. b) Schematic of proposed RO differentiation protocol using the growth factors involved in the neural induction of RPE to achieve an expedited neural induction within 2 to 6 days. These neural cells will then be lifted and seeded in suspension, where they will grow and mature into uniform-sized RO progenitors by D15.

Buchholz et al. (2013) established a short, efficient protocol to induce a neural fate when generating another ocular cell type, retinal pigmented epithelium (RPE), but these expedited steps have yet to be applied to RO production (Figure 2). This study aims to determine whether the growth factors used in the neural induction of stem cells in the RPE differentiation protocol could be substituted into the RO differentiation protocol and be used to create ROs more efficiently. This would introduce a shorter neural induction period and potentially increase the efficiency of RO differentiation (Figure 1a). Therefore, this study tests the hypothesis that a four-day neural induction period developed previously can be used as an alternative to the two-week-long neural induction period of the current protocol and bypass the need for manual dissection (Buchholz et al. 2013) (Figure 1b).

Figure 2. Retinal Pigment Epithelium (RPE) differentiation protocol. Schematic of protocol developed by Buchholz, et al. (2013) and Leach et al. (2015) that includes a four-day neural induction period using the growth factors and small molecules noggin, DKK1, IGF-1, NIC and bFGF.

Methods and Materials

Human embryonic stem cell (hESC) culture

We thawed human embryonic stem cell line H9 (WiCell Research Institute, Madison, WI) and plated the cells on 6-well plates coated with hESC-qualified Matrigel (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ). Cells were cultured in mTeSR Plus medium (StemCell Technologies, British Columbia, Canada) and media was changed every other day to promote health and maintain pluripotency. The cell culture dissociation reagent TrypLE (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) was used for passaging when cells were estimated to be 80% confluent by visual assessment. H9 cells were passaged onto 6-well plates containing 10µM rho-associated protein kinase (ROCK) inhibitor, Y-27632 (StemCell Technologies). Colonies were confirmed by microscopy to have no visible differentiated cells prior to passaging.

Determining the timing of neural induction using different seeding densities and addition of growth factors

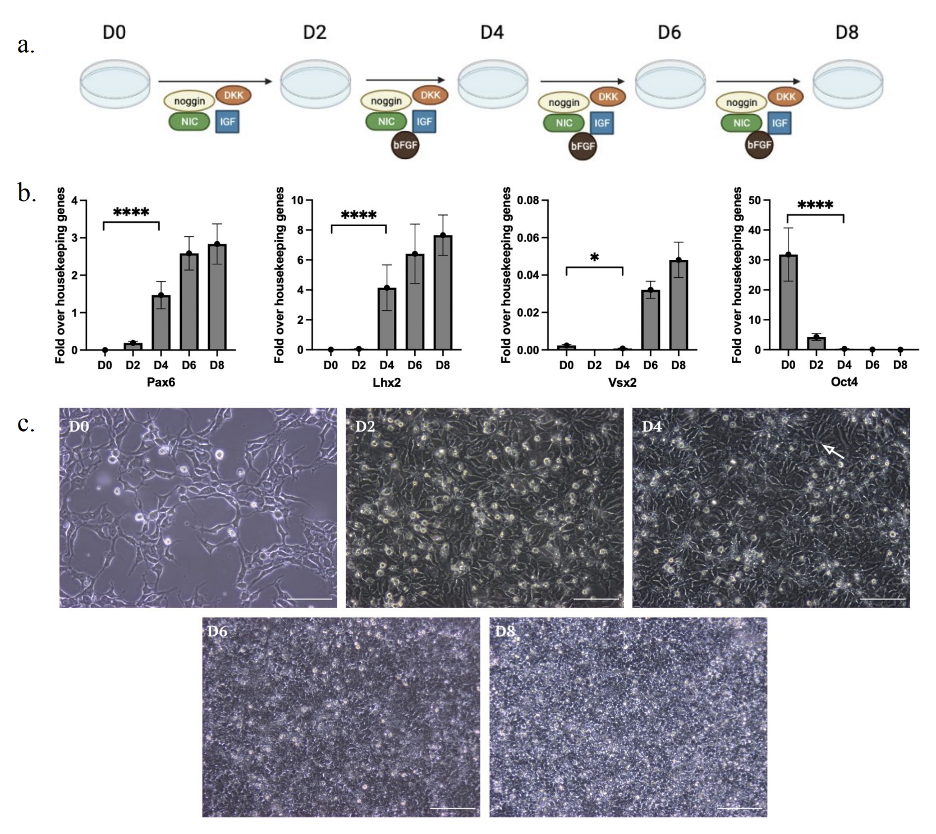

H9 stem cells were passaged and seeded directly onto Matrigel Basement Membrane Matrix-coated (Corning, Corning, NY) 6-well plates containing 10µM ROCK inhibitor (Y27632) (Thermo Fisher Scientific) at a density of 1.5 × 105 cell/cm2 and 3 × 105 cell/cm2. These densities were chosen because previous results suggested that the two seeding densities (1.5 × 105 cell/cm2 and 3 × 105 cell/cm2) influenced viability in the culture of ocular cell types (Lane et al. 2014). This study aims to further explore these effects, as the specific impact on viability—whether positive or negative—has not been fully characterized. These cells were grown in Retinal Differentiation Medium (RDM) throughout neural induction, which consists of DMEM/F12 (Thermo Fisher Scientific), 1X B27 minus Vitamin A (Thermo Fisher Scientific), 1X N2 (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and 1X non-essential amino acids (NEAA) (Thermo Fisher Scientific). From day 0 to day 1, following a previously described protocol by Buchholz et al. (2013), cells were cultured in RDM supplemented with 10mM nicotinamide (SigmaAldrich, St. Louis, MO), 50 ng/mL Noggin (Thermo Fisher Scientific), 10ng/mL Dickkopf-related Protein-1 (Dkk1) (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and 10ng/mL insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) (Thermo Fisher Scientific). From day 2 to day 8, cells were cultured in RDM supplemented with 10mM nicotinamide, 10 ng/mL Noggin, 10 ng/mL Dkk1, 5 ng/mL Basic Fibroblast Growth factor (bFGF) (Peprotech, Rocky Hill, NJ) and 10 ng/mL IGF-1 (Figure 3a). Samples from both seeding densities were harvested on days 0, 2, 4, 6 and 8 for RT-qPCR analysis. Images were taken on days 0, 2, 4, 6 and 8 using phase contrast microscopy.

Figure 3. hESCs are neurally inducted by D4 of differentiation. a) Schematic of the experimental approach to investigate the optimal time period for hESCs to differentiate towards a neural fate. b) Pax6 and Lhx2 expression upregulated, and Oct4 downregulated by D4 of differentiation. Error bars indicate standard deviation. c) hESCs acquire neural rosette morphology by D4 of differentiation (white arrow). Scale bar is 100μm.

Determining the optimal period to culture in suspension for neural induction

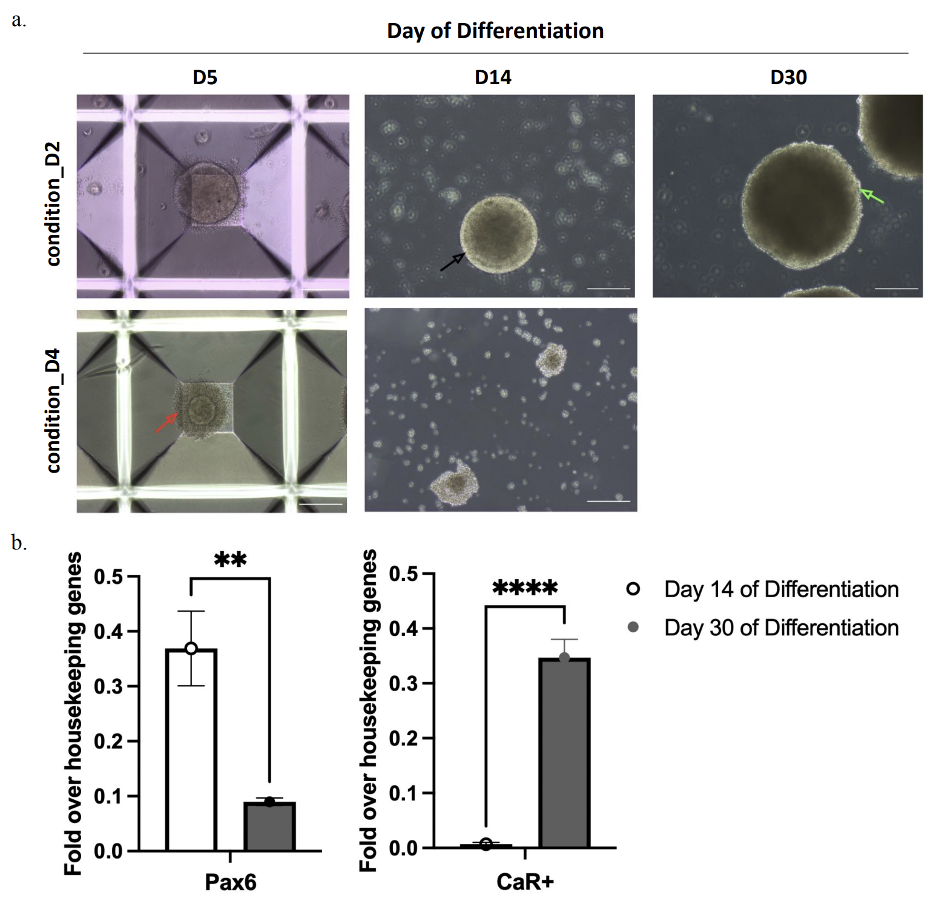

ROs are 3D structures initially grown in 2D culture. Therefore, early on in culture, the cells grown in 2D culture must be transferred to suspension to facilitate development of 3D aggregates which then develop into ROs. To determine the best time to transfer cells to suspension culture, cells were transferred to suspension culture on day 2 and day 4 of differentiation. On day 2 of differentiation, cells were lifted and seeded in suspension onto a 24-well AggrewellTM (StemCell Technologies, British Columbia, Canada) at a density of 900,000cells/well, with 10µM ROCK inhibitor (Y27632) (Thermo Fisher Scientific) to induce aggregate formation (condition_D2). Aggregates then continued with the differentiation protocol described previously with 10 mM nicotinamide, 10 ng/mL Noggin, 10 ng/mL Dkk1, 5 ng/mL bFGF and 10 ng/mL IGF-1 until day 4 (Figure 4). In condition_D4, cells were left to differentiate in 2D 6-well plates until day 4 before being seeded in suspension onto a 24-well AggrewellTM (StemCell Technologies). Following day 4, aggregates of both conditions were grown in RDM 2, which consists of DMEM/F12 (Thermo Fisher Scientific), DMEM (Thermo Fisher Scientific), 2% B27 with Vitamin A (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and 1% NEAA (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Media was changed on the aggregates every three days and allowed to grow until they reached an approximate diameter of 300μm, which occurred after five days in culture for condition_D2. Aggregates were then transferred into ultra-low attachment plates (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and grown in long-term culture until day 30 (Figure 4). Aggregates in condition_D4 were not able to reach a diameter of 300μm and were subsequently transferred to ultra-low attachment plates after 9 days in culture. Samples of both conditions were harvested on days 14 and 30 for RT-qPCR analysis. Images were taken every three days using phase contrast microscopy.

Figure 4. Schematic of the experimental approach to investigate optimal timing of aggregate formation. Stem cells were seeded at 1.5 × 105 cell/cm2 in RDM supplemented with noggin, DKK1, NIC, IGF-1 and bFGF from D0 to D4. In condition_D2, cells were transferred to 24-well aggrewells on D2, and in condition_D4, cells were transferred to 24-well aggrewells on D4. RNA samples were taken from both conditions on D14 and D30 for qPCR.

Reverse transcription - Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-qPCR)

Lysates for RNA purification were produced by triturating the cells and organoids in RLT lysis buffer (Qiagen, Germantown, MD). Samples were stored at -80℃, thawed and homogenized using QIAshredder columns (Qiagen). RNA was purified with the RNeasy kit (Qiagen) and treated with RNase-free DNase to conduct on-column digestion of genomic DNA. Reverse transcription was performed using the Applied Biosystems AG-pathID One Step PCR kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Each of the following TaqMan primer-probe sets were used (all Thermo Fisher Scientific): EIF2B2 (Hs00204540_m1), SERF2 (Hs00428481_m1), UBE2R2 (Hs00215107_m1), OCT4 (Hs00999632_g1), PAX6 (Hs01088114_m1), LHX2 (Hs00180351_m1), VSX2 (Hs01584046_m1), CaR+ (Hs01392360_m1) and POU4F2 (Hs00231820_m1). Gene expression was then quantified using BioRad CFX Real-Time PCR detection software. Gene expression was analyzed and normalized as the fold-over the geomean of housekeeping genes (EIF2B2, SERF2, UBE2R2).

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 9. Significance was defined as p < .05(*), p < .01(**), p < .001(***) and p < .0001(****). T-tests (two-tailed, unpaired) were used for comparisons between two groups. Groups of three or more were compared using one-way ANOVA.

Results

Optimizing growth factor addition: stem cells are neurally inducted by D4 of differentiation

Morphology and gene expression were assessed on D0, D2, D4, D6 and D8 of differentiation. The effect of this differentiation protocol on the expression of genes abundant in stem cells (Oct4), neural progenitor cells (Pax6, Lhx2) and neural retinal cells (Vsx2) was evaluated using qPCR. Cells at D4 of differentiation yielded optimal results as morphology and gene expression were consistent with neural cells. This was the earliest time period to exhibit no detectable expression of pluripotency marker Oct4 while maintaining high expression of neural markers Pax6 and Lhx2 (Figure 3b). Expression levels of all marker genes on D4 were significantly different from D0 (p < .001). This time point also exhibited signs of neural rosette formation, which are circular arrangements of cells that often mark the development of neural progenitors, and maintained closely packed colonies typical of neural cell colonies (Figure 3c). Conversely, samples from the D2 time point expressed higher levels of Oct4 and near-undetectable levels of Pax6 and Lhx2 compared to the D4 time point, suggesting that these cells have not undergone neural induction (Figure 3b). Expression levels of marker genes on D2 were also not significantly different from D0 (p > .05), with the exception of Oct4 (p < .0001). Samples from the D6 and D8 time points exhibited slightly higher expression of Pax6 and Lhx2 than the D4 time points, indicating no significant changes in neural gene expression compared to D4 (p > .05) (Figure 3b). Expression of neural retina marker Vsx2 was not detected in abundance at any of the assayed time points (Figure 3b). Cells at D0 and D2 maintained more loosely packed fibroblastic morphology consistent with hESCs, while samples from the D6 and D8 time points retained more tightly compact morphological characteristics compared to the D4 time point (Figure 3c). Increased expression of neural gene markers (Lhx2 and Pax6) and the presence of neural rosettes suggest that these samples have begun neural differentiation by D4 of differentiation.

Optimizing seeding density: seeding density does not significantly affect expression of Pax6 and Lhx2

To determine the optimal seeding density for inducing hESCs to differentiate into a neural fate, cells seeded at two densities were tested: 1.5 × 105 cells/cm2 and 3 × 105 cells/cm2. Morphology and gene expression were assessed on samples harvested on D0, D2, D4, D6 and D8 at each seeding density (Figure 5a).

Figure 5. Seeding density does not significantly impact neural induction. a) Schematic of the experimental approach to investigate optimal seeding density for neural differentiation. Stem cells were seeded at 1.5 × 105 cells/cm2 and 3 × 105 cells/cm2 in RDM supplemented with noggin, DKK1, NIC, IGF-1 and bFGF. b) Pax6, Lhx2 and Oct4 expression levels do not significantly differ based on seeding density on D4. Error bars indicate standard deviation. c) No notable morphological differences between seeding densities on D4. Scale bar is 200μm.

The effect of the two seeding densities on the expression of genes abundant in stem cells (Oct4), neural progenitor cells (Pax6, Lhx2) and neural retina (Vsx2) was evaluated using qPCR on D0, D2, D4, D6 and D8. The two different seeding densities did not significantly affect neural induction, as demonstrated by similar levels of expression of neural marker genes Pax6 and Lhx2 and pluripotency marker Oct4 on D4 of differentiation (p > .05) (Figure 5b). Furthermore, colonies at both seeding densities exhibited similar morphology on D4, although the 3 × 105 cells/cm2 density exhibited more detached cells as observed through microscopy (Figure 5c). There was a significant difference in the expression of neural retina marker Vsx2 between the two seeding densities (p < .05) (Figure 5b). However, Vsx2 was not detected in abundance at any of the assayed seeding densities (Figure 5b). These data suggest that the two seeding densities tested do not significantly affect the expression of neural genes. The 1.5 × 105 cells/cm2 density was selected for subsequent experiments to conserve cell stock.

Determining optimal timing for aggregate formation: seeding cells into aggrewells on D2 yields intact neural spheres

Phase contrast images from condition_D2 indicate formation of spherical aggregates one day after the cells were seeded in suspension (day 5 of differentiation) (Figure 6a). These spheres later developed a phase-bright outer ring and defined borders nine days after transfer into ultra-low attachment plates (day 14 of differentiation). However, spheres eventually developed darker centers and rougher edges (day 30 of differentiation) (Figure 6a). Microscopy images taken of aggregates in condition_D4 revealed that the spherical aggregates created in the AggrewellsTM were consistently smaller than the aggregates in condition_D2. These aggregates also exhibited residual cell debris (day 9 of differentiation). These spherical structures later dissociated into smaller clumps of cells and did not seem to contain any observable cell organization five days after seeding into ultra-low attachment plates (day 14 of differentiation) (Figure 6a).

Figure 6. condition_D2 yields intact aggregates with low expression of retinal progenitor marker genes. a) After 14 days of differentiation in condition_D2, aggregates have formed a phase bright outer rim and defined borders (black arrow). Top right image: Spheroids have developed darker centers and uneven borders after 30 total days of differentiation (green arrow). Bottom left image: In condition_D4, spherical aggregates have formed within aggrewells which are much smaller in size (red arrow). Scale bar is 200μm. b) Pax6 expression peaked on day 14 of differentiation and subsequently decreased significantly by Day 30. CaR+ expression peaked on day 30 of differentiation. Error bars indicate standard deviation.

The effect of transferring these cells at different time points was assessed by examining the expression of genes abundant in neural progenitor cells (Pax6), neural retina (Vsx2), amacrine cells (CaR+) and retinal ganglion cells (Brn3a). Calbindin 2 (CaR+) is a calcium-binding protein, and Brn3a (Pou4f2) is a transcription factor involved in maintaining visual system neurons in the retina. Samples collected from condition_D2 yielded low expression of Pax6 and CaR+, as well as the presence of intact neural spheres (Figures 6a and 6b). Pax6 expression was highest nine days after neural spheres were seeded into ultra-low attachment plates (day 14 of differentiation), and CaR+ expression levels were highest 25 days after seeding into ultra-low attachment plates (day 30 of differentiation). Expression levels of Pax6 and CaR+ differed significantly between D14 and D30 (p < .01). However, expression of both genes was below housekeeping gene expression (Figure 6b). Vsx2 and Pou4f2 expression were not detected at either time point. Conversely, the samples collected from condition_D4 did not contain sufficient RNA for downstream processing, and further qPCR analysis could not be conducted. Therefore, transferring cells from 6-well plates into suspension conditions on D2 of differentiation was the ideal time period to yield intact neural spheres.

Discussion

This study is the first to attempt to use an expedited neural induction period to produce hESC-derived RO progenitors. It was demonstrated that hESCs cultured until D4 in neural induction medium exhibited high expression of neural markers (Lhx2 and Pax6) while maintaining the neural rosette morphology characteristic of cells committing to a neural fate. This suggests that these samples had begun neural differentiation by D4 of differentiation. Interestingly, transferring cells from adherent culture to suspension conditions on D2 of differentiation (and not on D4) was more optimal to yield spherical aggregates at 1-day post-seed, which then exhibited a phase bright outer rim and defined borders by D14 of differentiation. Therefore, supplementing the media with growth factors following a 4-day neural induction period and moving cells from adherent culture to suspension culture on D2 resulted in the highest yield of RO progenitors.

We determined that an essential parameter for the culture of neural spheres is to move hESCs from 6-well plates (adherent culture) into suspension on D2 of differentiation. Aggregates formed from this condition grew in size over the course of culture and maintained morphology consistent with intact spheres containing distinct internal cell organization. However, by D30, these aggregates diverged from the expected appearance of ROs and began to develop darker centers and uneven borders, which is a morphology consistent with poor cell survival and lack of organization. This is also demonstrated by the low expression of Pax6, CaR+, Pou4f2 and Vsx2, which suggests that these organoids contained few, if any, retinal progenitor cells at the assayed time points (Figure 6b). Cells that were moved from adherent culture to suspension on D4 of differentiation formed aggregates that were substantially reduced in size with low cell viability. Further culture caused these aggregates to dissociate; there were no intact aggregates in this condition by D14 of culture (Figure 6a).

To our knowledge, our study is the first to establish that the successful aggregation of cells from adherent culture into suspensions is highly dependent on the stage of neural differentiation of the cells. As there were large differences in Pax6 and Lhx2 expression between D2 and D4 of culture (Figure 3b), it is possible that upregulation of these genes on D4 influenced downstream pathways that prevented the successful aggregation in condition_D4. This result is relevant to other studies attempting to characterize the role that neural genes play in the downstream pathways that lead to the further specification of the eye field (Diacou et al. 2022).

Another important parameter for efficient production of organoids is the incubation of differentiation cells in neural induction medium until D4. Incubation for shorter (D0 and D2) or longer (D6 and D8) periods is not as optimal. At D4, there was no Oct4 expression and sufficient expression of neural markers to suggest that the stem cells had been induced to adopt a neural fate. The presence of neural rosettes by D4 further confirms this conclusion (Figure 3c). Samples assessed before or after this time point either exhibited higher expression levels of the pluripotency marker Oct4 or exhibited only slightly elevated levels of neural marker genes respectively when compared to D4 (Figure 3b). However, as Vsx2 expression levels remained low throughout the eight days of differentiation, it could not be concluded whether these neural cells had been induced to differentiate into the neural retina (Figure 3b).

Our study is one of the first to investigate the gene expression profile of a modified neural induction protocol to generate ROs. This relates to other studies that are working to develop more efficient neural induction protocols applicable to the production of other neuronal or retinal cell types (Ji et al. 2019). Our gene expression results are consistent with reported findings that Pax6 and Lhx2 are upregulated early in neural differentiation, while Vsx2 expression is typically expressed at a later time period beginning anywhere from D10 to D30, depending on the differentiation protocol (Buchholz et al. 2013; Zhong et al. 2014; Meyer et al. 2009; Regent et al. 2019).

The final investigated parameter suggested that the 1.5 × 105 cell/cm2 and 3 × 105 cell/cm2 seeding densities did not have a significant impact on the neural induction of hESCs, as the expression of Pax6, Lhx2 and Oct4 were nearly identical across both seeding densities (Figure 5b). Vsx2 expression was significantly different across the two densities. However, the low expression of Vsx2 prevents any conclusions from being drawn. Microscopy results also suggest that the two seeding densities exhibited similar morphology and confluence (Figure 5c). At the 3 × 105 cell/cm2 density, more detached cells were observed by microscopy, which may suggest a higher frequency of cell death at this density. However, a cell-death assay would need to be conducted to determine whether there is a significant difference in viability between the two densities. While no significant differences were detected between the two densities, a lower seeding density would align with more efficient and scalable manufacturing practices that would lower the initial cost of the reagents and growth factors used in the manufacture (Gottipamula et al. 2013; Wragg et al. 2019). Protocols requiring fewer cells will conserve frozen banks of cell stocks, which will be important when manufacturing cell-based therapies for the clinic. From this perspective, the 1.5 × 105 cells/cm2 density would be more efficient at a clinical level.

Limitations

Morphological observations of organoids from condition_D2 on D30 of culture are consistent with previous studies that have found that successful RO differentiation is highly dependent upon nutrient availability. Due to the lack of vascularization in ROs, there is limited passive diffusion of nutrients and oxygen/CO2, often leading to degeneration of the innermost layers in long-term culture (Akhtar et al. 2019; Reichman et al. 2014). The dark centers present in condition_D2 suggest a similar phenomenon where essential nutrients present in the culture medium could not reach the innermost cells as they grew, which led to low expression of neural marker genes on D30. Viability assays will need to be conducted to confirm that the darker centers are caused by the death of the innermost cells. It is possible that this phenomenon was exacerbated by the fact that the size of the neural spheres on D30 were substantially larger than ROs at a comparable stage of differentiation. One potential explanation for this is that a high proportion of organoids fused with surrounding organoids throughout the culture period, resulting in diameters greater than 300μm. Studies on both cerebral organoids and ROs have found that using a spinning bioreactor during differentiation prevents aggregation of organoids while also improving the diffusion of nutrients and O2, resulting in a higher yield of organoids (DiStefano et al. 2021; Qian et al. 2018). Therefore, further experimentation using medium formulations higher in nutrient concentration or bioreactor-like structures to keep neural spheres separated may be investigated to improve the long-term viability of these aggregates.

Studies have also documented that ROCK inhibition (supplementing medium with Y27632) not only promotes the survival of dissociated stem cells but also plays a role in cytoskeletal and tissue self-organization, as well as epigenetic regulation in the early stages of human neurogenesis (Compagnucci et al. 2016; Xue et al. 2012). Early RO morphological data have revealed that the addition of 20μM of Y27632 into culture medium for the first 48 hours of differentiation improved the yield, size and cellular organization of resulting early-stage ROs (Mellough et al. 2019). Implementation of this step into our protocol may improve the morphological characteristics of expedited organoids formed from both condition_D2 and condition_D4.

In addition, the low expression of amacrine and retinal ganglion cell marker genes (CaR+, Pou4f2) is consistent with previous findings that retinal progenitors such as amacrine and retinal ganglion cells do not begin development until week 6 and week 8 of RO differentiation (Zhong et al. 2014; Capowski et al. 2018). Therefore, it is possible that the organoids cultured in this study did not contain the necessary structures or organization required to develop retinal progenitor cells at the assayed time points (D14 and D30 of differentiation), and further analysis is needed to evaluate the expression of these genes at a later time point. One study demonstrated through immunostaining that marker proteins for distinct cell types such as bipolar cells (VSX2), amacrine cells (PAX6) and retinal ganglion cells (BRN3) were present at low levels by D32 of RO differentiation, so immunostaining of the expedited organoids at comparable time points may yield further insights into the cellular environment of these structures (Brooks et al. 2019).

Studies have also shown that in the development of the native human retina, formation of the optic cup and neural retina (Vsx2) occur a few days after the development of the early eye field (Pax6, Lhx2) (Zhong et al. 2014). However, as cells from the neural retina will eventually develop into the different cell types typically found in ROs such as amacrine and retinal ganglion cells, upregulation of Vsx2 early on in neural differentiation is key to producing intact neural spheres that could eventually develop into ROs (Clegg et al. 2008). Without confirmation of Vsx2 expression, it could not be concluded whether these cells had been induced to adopt a neural retinal fate specifically or had just been induced to adopt another neural eye-field cell type. Future studies could further explore the length of time that cells are cultured in neural induction medium and consider postponing the seeding of neurally induced cells into suspension until Vsx2 is upregulated at a later time point. Further, it has been shown that early-eye field cells undergoing differentiation into the neural retina first express Mitf as cells are specified into the optic vesicle, followed by subsequent repression of Mitf coinciding with the upregulation of Vsx2 as cells complete differentiation into neural retina (Meyer et al. 2009). Therefore, to better follow the differentiation pathway of these hESCs, a time-course evaluation of Mitf and Vsx2 expression using our neural induction protocol would be helpful. Future studies could also investigate alternative growth factors that could upregulate Vsx2 expression early on in differentiation, such as Activin A, Fibroblast Growth Factor 1 (FGF1) or other proteins in the FGF family (Regent et al. 2019; Lu et al. 2017; Pittack et al. 1997; Zagozewski et al. 2014). Alternatively, the concentration of bFGF could be increased, as studies have found that supplementing medium with 20 ng/mL to 50 ng/mL of bFGF within the first few days of differentiation yielded robust Vsx2 expression one-week post-induction (Zhao et al. 2016; Ng et al. 2015).

Previous studies have found that seeding density leads to significant differences in cell yield and the expression of retinal genes such as Mitf and Best1 in the differentiation of hESC-RPE (Lane et al. 2014). Lane et al. (2014) seeded cells from 17,000 to 100,000 per cm2 and found that higher-density environments led to higher differentiation efficiency and higher expression of retinal genes. As our study did not detect significant differences in gene expression at similar seeding densities, it is possible that the seeding density conditions of this study were too similar to observe differences in gene expression. Therefore, future studies could investigate a broader range of seeding densities in order to further elucidate the role of seeding density in differentiation efficiency and the gene expression of neural markers.

Conclusion

This report is the first to use an expedited neural induction protocol to investigate the parameters required for efficient neural induction for RO production. It was concluded that hESCs are induced into a neural fate on D4 of differentiation using a neural induction protocol developed by Buchholz et al. (2013) and that transferring cells from adherent culture to suspension conditions on D2 was key in creating intact organoids. Furthermore, seeding hESCs at 1.5 × 105 cell/cm2 and 3.0 × 105 cell/cm2 did not cause significant differences in gene expression. The conclusions from this study can be extended to the differentiation of ROs to expedite the process of neural induction while also producing more uniformly-sized organoids, which would reduce variability and confounding factors in RO studies. This would allow researchers to gain timely insights into various retinal processes and expedite essential RO-based retinal therapies for degenerative retinal diseases such as AMD and diabetic retinopathy.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank my mentors, who helped make this study possible. I am grateful to my mentor, Britney Pennington, for training me in cell culture and for guiding me through all stages of this project. I would also like to thank Mohamed Faynus, Mika Katsura and the rest of Clegg Lab for providing valuable insights into the differentiation of retinal organoids. This work was funded by the UCSB Undergraduate Research and Creative Activities Grant (URCA).

References

Aasen, D. M., and Vergara, M. N. (2020). New drug discovery paradigms for retinal diseases: A focus on retinal organoids. Journal of Ocular Pharmacology and Therapeutics, 36(1), 18-24.

Akhtar, T., Xie, H., Khan, M. I., Zhao, H., Bao, J., Zhang, M., & Xue, T. (2019). Accelerated photoreceptor differentiation of hiPSC-derived retinal organoids by contact co-culture with retinal pigment epithelium. Stem Cell Research, 39, 101491.

Allison, K., Patel, D., & Alabi, O. (2020). Epidemiology of glaucoma: The past, present, and predictions for the future. Cureus.

Armento, A., Murali, A., Marzi, J., Almansa-Garcia, A. C., Arango-Gonzalez, B., Kilger, E., Clark, S. J., Schenke-Layland, K., Ramlogan-Steel, C. A., Steel, J. C., & Ueffing, M. (2021). Complement factor H loss in RPE cells causes retinal degeneration in a human RPE-porcine retinal explant co-culture model. Biomolecules, 11(11), 1621.

Bird, A. (2020). Role of retinal pigment epithelium in age-related macular disease: A systematic review. British Journal of Ophthalmology, 105(11), 1469-1474.

Brooks, M. J., Chen, H. Y., Kelley, R. A., Mondal, A. K., Nagashima, K., Val, N. D., Li, T., Chaitankar, V., & Swaroop, A. (2019). Improved retinal organoid differentiation by modulating signaling pathways revealed by comparative transcriptome analyses with development in vivo. Stem Cell Reports, 13(5), 891-905.

Buchholz, D. E., Pennington, B. O., Croze, R. H., Hinman, C. R., Coffey, P. J., & Clegg, D. O. (2013). Rapid and efficient directed differentiation of human pluripotent stem cells into retinal pigmented epithelium. Stem Cells Translational Medicine, 2(5), 384-393.

Capowski, E. E., Samimi, K., Mayerl, S. J., Phillips, M. J., Pinilla, I., Howden, S. E., Saha, J., Jansen, A. D., Edwards, K. L., Jager, L. D., Barlow, K., Valiauga, R., Erlichman, Z., Hagstrom, A., Sinha, D., Sluch, V. M., Chamling, X., Zack, D. J., Skala, M. C., & Gamm, D. M. (2018).

Chen, L. J., Ito, S., Kai, H., Nagamine, K., Nagai, N., Nishizawa, M., Abe, T., & Kaji, H. (2017). Microfluidic co-cultures of retinal pigment epithelial cells and vascular endothelial cells to investigate choroidal angiogenesis. Scientific Reports, 7(1).

Clegg, D. O., Buchholz, D., Hikita, S., Rowland, T., Hu, Q., & Johnson, L. V. (2008). Retinal pigment epithelial cells: Development in vivo and derivation from human embryonic stem cells in vitro for treatment of age-related macular degeneration. Stem Cell Research and Therapeutics, 1-24.

Compagnucci, C., Barresi, S., Petrini, S., Billuart, P., Piccini, G., Chiurazzi, P., Alfieri, P., Bertini, E., & Zanni, G. (2016). Rho kinase inhibition is essential during in vitro neurogenesis and promotes phenotypic rescue of human iPSC-derived neurons with oligophrenin-1 loss of function. Stem Cells Translational Medicine, 5(7), 860-869.

Diacou, R., Nandigrami, P., Fiser, A., Liu, W., Ashery-Padan, R., & Cvekl, A. (2022). Cell fate decisions, transcription factors and signaling during early retinal development. Progress in Retinal and Eye Research, 91, 101093.

Diakatou, M., Dubois, G., Erkilic, N., Sanjurjo-Soriano, C., Meunier, I., & Kalatzis, V. (2021). Allele-specific knockout by CRISPR/Cas to treat autosomal dominant retinitis pigmentosa caused by the G56R mutation in NR2E3. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 22(5), 2607.

Distefano, T. J., Chen, H. Y., Panebianco, C., Kaya, K. D., Brooks, M. J., Gieser, L., Morgan, N. Y., Pohida, T., & Swaroop, A. (2021). Accelerated and improved differentiation of retinal organoids from pluripotent stem cells in rotating-wall vessel bioreactors. Stem Cell Reports, 16(1), 224.

Gottipamula, S., Muttigi, M. S., Chaansa, S., Ashwin, K. M., Priya, N., Kolkundkar, U., Raj, S. S., Majumdar, A. S., & Seetharam, R. N. (2013). Large-scale expansion of pre-isolated bone marrow mesenchymal stromal cells in serum-free conditions. Journal of Tissue Engineering and Regenerative Medicine, 10(2), 108-119.

Ji, S. L., & Tang, S. B. (2019). Differentiation of retinal ganglion cells from induced pluripotent stem cells: A review. International Journal of Ophthalmology.

Kruczek, K., Qu, Z., Gentry, J., Fadl, B. R., Gieser, L., Hiriyanna, S., Batz, Z., Samant, M., Samanta, A., Chu, C. J., Campello, L., Brooks, B. P., Wu, Z., & Swaroop, A. (2021). Gene therapy of dominant CRX-Leber congenital amaurosis using patient stem cell-derived retinal organoids. Stem Cell Reports, 16(2), 252-263.

Lane, A., Philip, L. R., Ruban, L., Fynes, K., Smart, M., Carr, A., Mason, C., & Coffey, P. (2014). Engineering efficient retinal pigment epithelium differentiation from human pluripotent stem cells. Stem Cells Translational Medicine, 3(11), 1295-1304.

Leach, L. L., Buchholz, D. E., Nadar, V. P., Lowenstein, S. E., & Clegg, D. O. (2015). Canonical/β-catenin Wnt pathway activation improves retinal pigmented epithelium derivation from human embryonic stem cells. Investigative Ophthalmology and Visual Science, 56(2), 1002-1013.

Lu, A. Q., Popova, E. Y., & Barnstable, C. J. (2017). Activin signals through Smad2/3 to increase photoreceptor precursor yield during embryonic stem cell differentiation. Stem Cell Reports, 9(3), 838-852.

Mellough, C. B., Collin, J., Queen, R., Hilgen, G., Dorgau, B., Zerti, D., Felemban, M., White, K., Sernagor, E., & Lako, M. (2019). Systematic comparison of retinal organoid differentiation from human pluripotent stem cells reveals stage-specific, cell line, and methodological differences. Stem Cells Translational Medicine, 8(7), 694-706.

Meyer, J. S., Shearer, R. L., Capowski, E. E., Wright, L. S., Wallace, K. A., McMillan, E. L., Zhang, S. C., & Gamm, D. M. (2009). Modeling early retinal development with human embryonic and induced pluripotent stem cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 106(39), 16698-16703.

Ng, T. K., Yung, J. S., Choy, K. W., Cao, D., Leung, C. K., Cheung, H. S., & Pang, C. P. (2015). Transdifferentiation of periodontal ligament-derived stem cells into retinal ganglion-like cells and its microRNA signature. Scientific Reports, 5(1).

Petters, R. M., Alexander, C. A., Wells, K. D., Collins, E. B., Sommer, J. R., Blanton, M. R., Rojas, G., Hao, Y., Flowers, W. L., Banin, E., Cideciyan, A. V., Jacobson, S. G., & Wong, F. (1997). Genetically engineered large animal model for studying cone photoreceptor survival and degeneration in retinitis pigmentosa. Nature Biotechnology, 15(10), 965-970.

Pittack, C., Grunwald, G. B., & Reh, T. A. (1997). Fibroblast growth factors are necessary for neural retina but not pigmented epithelium differentiation in chick embryos. Development, 124(4), 805-816.

Qian, X., Jacob, F., Song, M. M., Nguyen, H. N., Song, H., & Ming, G. L. (2018). Generation of human brain region-specific organoids using a miniaturized spinning bioreactor. Nature Protocols, 13(3), 565-580.

Regent, F., Morizur, L., Lesueur, L., Habeler, W., Plancheron, A., Ben, M., Barek, K., & Monville, C. (2019). Automation of human pluripotent stem cell differentiation toward retinal pigment epithelial cells for large-scale productions. Scientific Reports, 9(1).

Reichman, S., Terray, A., Slembrouck, A., Nanteau, C., Orieux, G., Habeler, W., Nandrot, E. F., Sahel, J. A., Monville, C., & Goureau, O. (2014). From confluent human iPS cells to self-forming neural retina and retinal pigmented epithelium. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 111(23), 8518-8523.

Schnichels, S., Paquet-Durand, F., Löscher, M., Tsai, T., Hurst, J., Joachim, S. C., & Klettner, A. (2021). Retina in a dish: Cell cultures, retinal explants and animal models for common diseases of the retina. Progress in Retinal and Eye Research, 81, 100880.

Vision impairment and blindness. (2022). World Health Organization.

Wong, W. L., Su, X., Li, X., Cheung, C. M., Klein, R., Cheng, C. Y., & Wong, T. Y. (2014). Lancet Global Health, 2(2).

Wragg, N. M., Player, D. J., Martin, N. R., Liu, Y., & Lewis, M. P. (2019). Development of tissue-engineered skeletal muscle manufacturing variables. Biotechnology and Bioengineering, 116(9), 2364-2376.

Xue, Z. W., Shang, X. M., Xu, H., Dong, T. W., Liang, C. H., & Yuan, Y. (2012). Rho-associated coiled kinase inhibitor Y-27632 promotes neuronal-like differentiation of adult human adipose tissue-derived stem cells. Chinese Medical Journal, 125(18), 3332-3335.

Zagozewski, J. L., Zhang, Q., & Eisenstat, D. D. (2014). Genetic regulation of vertebrate eye development. Clinical Genetics, 86(5), 453-460.

Zhang, X., Thompson, J. A., Zhang, D., Charng, J., Arunachalam, S., McLaren, T. L., Lamey, T. M., Roach, J. N. D., Jennings, L., McLenachan, S., & Chen, F. K. (2020). Characterization of CRB1 splicing in retinal organoids derived from a patient with adult-onset rod-cone dystrophy caused by the c.1892A>G and c.2548G>A variants. Molecular Genetics and Genomic Medicine, 8(11).

Zhang, X., Wang, W., & Jin, Z. B. (2021). Retinal organoids as models for development and diseases. Cell Regeneration, 10(1).

Zhao, J. J., & Afshari, N. A. (2016). Generation of human corneal endothelial cells via in vitro ocular lineage restriction of pluripotent stem cells. Investigative Ophthalmology and Visual Science, 57(15), 6878.

Zheng, Y., He, M., & Congdon, N. (2012). The worldwide epidemic of diabetic retinopathy. Indian Journal of Ophthalmology, 60(5), 428-428.

Zhong, X., Gutierrez, C., Xue, T., Hampton, C., Vergara, M. N., Cao, L. H., Peters, A., Park, T. S., Zambidis, E. T., Meyer, J. S., Gamm, D. M., Yau, K. W., & Canto-Soler, M. V. (2014). Generation of three-dimensional retinal tissue with functional photoreceptors from human iPSCs. Nature Communications, 5(1).