Author: Jon Ginsberg

Institution: Emory University

Date: April 2006

Abstract

Psychologists have devoted little attention to contemplating the effect of worry on the sleep patterns of college students. The purpose of this study is to address this gap by focusing on academic worries and its effect on length of sleep. It was proposed that students who have more academic worries would report less sleep than those who have less academic worries. It was also proposed that an increase in sleep disturbances attributed to worry would predict less sleep. To examine these hypotheses, college students were assessed on habitual sleep length, the Sleep Disturbance Ascribed to Worry Scale, and the Academic Stress Scale. Fifty-five students completed the measures. Support was found for both predictions. The results indicated that academic worry and sleep disturbance ascribed to worry were negatively correlated with sleep length. Regression analyses further indicated that academic worry does not predict sleep length above and beyond sleep disturbance ascribed to worry, and that academic worry was significantly negatively related to sleep length regardless of sleep disturbance ascribed to worry. The implications of these results are discussed, as are directions for future research.

Introduction

Getting a good night sleep under worrisome circumstances is often a problem for college students. The college campus is a seemingly stressful environment. In fact, we commonly hear individuals complain that they were up all night cramming for an examination, or worrying about various issues. Academic concerns pervade the lives of students, interrupting aspects of their daily routine. College life, characterized by the pressure to seek an appropriate identity, certainly presents an array of stressors (Stark and Traxler 1974; Whitbourne and Tesch 1985). Students are pressured to perform, pressured to fit in, pressured to commit, and pressured to live up to the expectations of others. They even set goals for themselves that are sometimes impossible to achieve. Forming an identity in a college environment is indeed difficult, as common worries can have significant behavioral consequences, particularly on sleep patterns. Psychologists, though, have devoted little attention to investigating the ramifications that academic worries have on sleep behaviors. In this study, the relevance of worry will be examined in relation to quality of sleep in undergraduate college students.

Previous research on the relationship between worry and sleep quality has not adequately addressed worry. Worry is often confused with the physiological activity of anxiety, yet they are separate constructs. McCann and Stewin (1988) suggest that worry is an uncontrollable process, a sequence of thoughts that attempts to settle predicaments that have uncertain and potentially negative outcomes. Anxiety, on the other hand, is the body's response to demand caused by stressful events (Verlander, Benedict, and Hanson 1999). It refers primarily to the awareness of bodily arousal. Thus, while worry is a cognitive activity, anxiety is a physiological activity.

Gana, Martin, and Canouet (2001) investigated the relationship between worry and anxiety. Although they found worry to significantly positively predict anxiety, they observed no effect in the opposite direction, providing evidence that these two constructs are different yet related. While worry may be the underlying mechanism of anxiety, it can have separate implications because the association between the two concepts is not bidirectional.

To assess sleep disturbance attributed to worry, past research has tended to focus on measures of anxiety rather than worry; this suggests that the two generate equivalent results. In a groundbreaking study, Hartmann, Baekeland, and Zwilling (1972) observed individual differences among 28 short sleepers (less than 6 hours) and 24 long sleepers (more than 9 hours). Although no measures of worry were utilized, they concluded that longer sleepers are worriers (critical, timid, and non-conformist), whereas shorter sleepers are nonworriers (ambitious, decisive, self-assured, and psychologically healthy).

Worry, however, was measured by evaluating nervousness and anxiety. In addition to the absence of a standardized measure of worry, the conclusions were solely based on subjective clinical observations. It is difficult to replicate impressions that are open to interpretation and derived from subjective evidence. Accordingly, the reliability of Hartmann et al.'s (1972) conclusions is questionable; thus, the need to verify their observations with psychometric tests is obvious. Furthermore, participants were limited to men who were recruited from newspaper advertisements. Since the sample was restricted and participation was voluntary, it is difficult to generalize the conclusions to a wider population.

Nevertheless, it was proposed that worrying was not a factor for short sleepers since they had better coping styles that tended to minimize stressors. Shorter sleepers, for instance, avoided problems through a process of denial that was fostered through their high activity levels. Hartmann et al. (1972) contended that short sleepers had no time to worry since they were hard at work and kept busy. High activity levels were thus viewed as a defense mechanism. The psychological differences between habitual short and long sleepers suggest that sleep-length requirements may be inextricably linked with attempts to cope with worrisome experiences.

More recent findings have been inconsistent and contradictory. Attempting to replicate the findings of Hartmann et al. (1972), several researchers have examined the anxiety levels of both short and long sleepers. These studies all found a negative correlation between anxiety and sleep length in various undergraduate populations (Hicks and Pellegrini 1977; Hicks, Pellegrini, and Hawkins 1979; Kumar and Vaidya 1984). It is difficult to accept these notions as undermining Hartmann et al.'s (1972) observations since they do not focus directly on worry. Can we assume that worry and anxiety are sufficiently related to be used interchangeably? Can anxiety have different effects on sleep than worry? Individuals who experience a general tendency to worry have been shown to often experience increased anxiety, but it is not acceptable to simply assume that the two constructs will always yield the same behavioral consequences (Gana, Martin, and Canouet 2001). Thus, the current study will clearly analyze the amount of worry experienced by college students, and examine the implications it has for sleep.

In studying sleep patterns, McCann and Stewin (1988) were the first researchers to independently assess worry and anxiety. They assessed worry by asking 106 students across three introductory level psychology courses to specify the amount of worry they normally feel. Participants indicated the degree to which they felt they were a worrier or nonworrier on a 9-point Likert scale. Anxiety, though, was evaluated on a much more extensive scale, using Speilberger, Gorsuch, and Lushene's (1970, as cited in McCann and Stewin 1988) State-Trait Anxiety Inventory. Students were also asked to indicate their preferred length of sleep in a 24-hour period. Although worry and anxiety were moderately correlated, r(104) = 0.43 (p less than 0.001), they did not have similar effects on sleep length. While worry was positively correlated with preferred length of sleep, r(104) = 0.16 (p less than 0.05), anxiety was not related to preferred length of sleep, r(104) = 0.07, (p less than 0.47). These results suggest that long sleepers are inclined to worry more than short sleepers, providing support for the conclusions of Hartmann et al (1972).

Despite a significant correlation between worry and anxiety, the results indicate the importance of separating worry and anxiety. Methodological problems, though, are apparent in their assessment. Rather than examining habitual sleep length, the researchers only considered preferred amount of sleep. Actual sleep length may have substantially differed from preferred sleep length. Furthermore, worry was assessed with one self-evaluation item. The validity of any single-item measurement of worry is questionable.

In an attempt to improve upon the methodologies in the McCann and Stewin study (1988), Kelly (2002) developed the Sleep Disturbance Ascribed to Worry Scale. This scale was specifically designed to evaluate the amount of sleep disturbance attributed to worry. The study further set out to clarify the relationship between worry and habitual sleep length with the use of the Worry Domains Questionnaire (Tallis, Eysenck, and Mathews 1992; as cited in Kelly 2002). Two-hundred and twenty-two college students completed the questionnaires and also indicated the amount of time that they habitually sleep in every 24-hour period. The results indicated that sleep length was significantly negatively correlated with the Worry Domains Questionnaire, r = -0.24 (p less than 0.01), as well as sleep disturbance attributed to worry, r = -.20 (p less than 0.01). Also, sleep disturbance attributed to worry and worry were positively correlated, r = 0.42 (p less than 0.01).

To further explore the notion that individuals who worry are susceptible to developing sleep disturbances, Kelly (2002) calculated a simple regression with worry as the predictor variable and sleep length as the criterion. Worry accounted for 6% of the variance in sleep length, F(1,220) = 13.50 (p less than 0.0001). College students who worry more seem to sleep less.

When evaluating worry amongst college students, it is essential to use a scale that is relevant in a college environment. The Worry Domain Questionnaire, though, lacks items that assess the presence of academic stressors. The items only tap five broad worry domains: relationships, lack of confidence, aimless future, work-related, and financial. Of course, these domains also apply to college students, but to ignore domains that are specific to academic life is insufficient when examining college students. For this reason, the current study intends to address this gap in understanding the relationship between worry and sleep in a college environment.

In order to further develop understanding of the Sleep Disturbance Ascribed to Worry Scale, Kelly (2003a) examined whether or not certain variables, such as anxiety and stress, related to sleep disturbance attributed to worry. It was proposed that the experience of worry coincides with anxiety, as well as perceived stress. Individuals with more sleep disturbances resulting from worry were found to be characterized by increased worry frequency, pathological worrying, perceptions of stress, and trait anxiety. Hence, worry, anxiety, and stress were foundational for sleep disturbance ascribed to worry to develop.

The extent to which sleep disturbance attributed to worry could be considered separate from anxiety was also investigated (Kelly 2003a). Worry was assessed with the Worry Domains Questionnaire, while anxiety was assessed with the Costello-Comrey Anxiety scale (Costello and Comrey 1967; as cited in Kelly 2003a). While holding worry constant, the Sleep Disturbance Ascribed to Worry Scale remained significantly correlated to sleep disturbance, r = 0.40 (p less than 0.0001), as well as anxiety, r = 0.30 (p less than 0.001). When holding anxiety constant, the Sleep Disturbance Ascribed to Worry Scale continued to significantly correlate with sleep disturbance, r = 0.39 (p less than 0.0001), but not with worry, r = 0.13 (p less than 0.18). This indicates that anxiety may mediate worry. Consequently, rather than worry and anxiety being manifestations of a single construct, it appears that they are related but separate.

Kelly's (2003a) findings question the direct influence of general worry on sleep disturbance attributed to worry. If ascribing sleep disturbance to worry, an individual seemingly must also experience worry. Nevertheless, individuals who experience sleep disturbance as a result of worry do not need to experience worry simultaneously with anxiety to attribute sleep disturbance to worry.

Worry can certainly be measured by a variety of factors, but the social and academic demands of undergraduate life greatly interfere with college sleep habits (McCann and Stewin 1988). Since Kelly (2003a) found a significant relationship between anxiety and sleep disturbance ascribed to worry, previous research on academic anxiety is relevant to the current study. In examining the anxiety levels of short and long sleeping college students, Hicks, Pellegrini, and Hawkins (1979) found that short sleepers were only more anxious than long sleepers when their anxiety was related to situations involving evaluation of their achievement in college. On the other hand, short and long sleepers did not show a significant difference in anxiety levels when assessed on a Death Anxiety Scale (Templer 1970; as cited in Hicks et al. 1979). Therefore, in order to better understand the relationship between worry and sleep among college students, it is essential to identify the specific sources of worry in a university setting.

College students encounter a host of potential stressors to worry about while attending a university. In the search for identity throughout college, individuals may come across the same stimuli, but deal with them in contrasting ways. Two individuals may appraise the same situation differently and have different emotional responses (Verlander, Benedict, and Hanson 1999). Erikson (1950, as cited in Muss 1996) asserted that some individuals within the same environment have a greater propensity to worry. This may lead to a poorer sense of personal identity, doubts about occupational skills, and an inability to resolve core psychological tasks.

Verlander et al. (1999) proposed that a college students' personal response to a stressful event can predict sleep patterns. They found that the emotional responses to stressors, such as worry and anxiety, were the best predictors of depth of sleep, difficulty in waking up, quality and latency of sleep, and sleep irregularity, rather than environmental events (e.g. health conditions) and personality mediators (e.g. ability to relax). Moreover, the experience of stress elicits the sleep disturbance that coincides with worry (Kelly 2003a). Hicks and Garcia (1987) have also assessed the effect of stress on sleep duration, contending that the increased presence of stressors reduces sleep. The decrease in sleep during periods of high stress can be accredited to higher than normal levels of both anxiety and worry (Hicks and Garcia 1987). They did not further differentiate between anxiety and worry, nor identify specific stressors.

Few researchers have investigated whether worry over specific domains of stressors would predict sleep patterns. Kelly (2003b) reexamined the effect of worry on sleep duration, using the Worry Domains Questionnaire to distinguish worry content associated with decreased sleep length in college students. The results indicated that work-related worries and financial difficulties did not predict decreased sleep. Only worry about relationships was associated with less sleep. Work-related worries were assumed to be equivalent to academic worries. However, this assumption could be called into question because occupational stressors differ from those found in an academic setting. Kelly (2003b) further suggests that academic worry is a significant stressor among college students, but that his sample may not have been worried about work/academic issues enough to affect sleep since participation in the study was voluntary. Thus, these results provide further evidence that a different scale should be used to examine worry among college students. Specifically, a scale should be employed that directly assesses academic stressors.

Considering various sources of worry in an academic setting will allow psychologists to better understand the complex relationship between worry and sleep among college students. While social and lifestyle worries have been extensively examined, academic worry has received minimal attention. Since recent findings have cast doubts on the findings of Hartmann et al. (1972) and McCann and Stewin (1988), it is hypothesized that students who have more academic worries will report less sleep than those who have less academic worries. It is also hypothesized that an increase in sleep disturbances attributed to worry will predict less sleep.

Method & Materials

Participants

Participants were 55 undergraduate college students at Emory University in Atlanta, Georgia. The sample was composed of 20 (36.4%) males and 35 (63.6%) females. Twenty-three (41.8%) Juniors and 15 (27.3%) Seniors participated in the study. Eight (14.5%) participants identified themselves as Freshman and nine (16.4%) identified themselves as Sophomore. Race and ethnicity were not recorded.

Design

Since the independent variable of academic worry was hypothesized to predict the dependent variable of sleep length, a correlational survey was chosen as the research strategy. The design was suitable to assess the ramifications that worry has on the sleep patterns of a general population of undergraduate students. Aside from allowing us to evaluate our prediction, the use of this technique permitted us to indicate whether or not the relationship between worry and sleep is consistent with recent research that has failed to reinforce the findings of Hartmann et al. (1972).

Measures The Sleep Disturbance Ascribed to Worry Scale. Kelly's (2002) Sleep Disturbance Ascribed to Worry (SAW) scale was used to assess sleep disturbances attributed to worry. The SAW has been the only scale developed as a specific measure of the attribution of sleep disturbance to worry, the effects of worry on sleep, and the frequency of sleep disturbance ascribed to worry. It consists of five items (i.e., "How often do you awaken from your normal sleeping time and are completely unable to return to sleep because of worry?") that are administered using an 11-point Likert scale, ranging from 0 (never) to 10 (very often). Higher scores on each item indicate greater levels of sleep disturbance ascribed to worry.

In order to determine the reliability of the SAW, internal consistency has been evaluated in three separate studies (Kelly 2002; Kelly 2003a). The coefficient alphas of the five items were satisfactory in all occasions, at 0.85, 0.87, and 0.89. To assess test-retest reliability, Kelly and Forbes (2004) administered the SAW to 116 college students twice over a one-month interval. The test-retest correlation was 0.83, further demonstrating satisfactory reliability. Kelly (2002) examined validity for the SAW by asking 46 participants to describe the general quality of their sleep on an 11-point Likert scale ranging from awful to great. There was a significant correlation between this quality of sleep question and SAW scores, r = -0.37 (p less than 0.01), signifying that validity was satisfactory.

Academic Stress Scale. In order to examine the presence of academic worry, the 35-item Academic Stress Scale was administered (Kohn and Frazer 1986). Since academic worry has received little attention and a considerable portion of a student's life is dedicated to the pursuit of academic endeavors, Kohn and Frazer's measure was deemed appropriate for this study. The Academic Stress Scale measures the degree of academic worry across three subscales: physical, psychological, and psychosocial. Physical stressors are environmental factors which influence behavior such as temperature, lighting, and noise. Psychological stressors refer to the irrational interpretation of events that result in emotional consequences (e.g., final grades, studying for an examination, and reading wrong material). Psychosocial stressors refer to interpersonal interactions which affect the behavior of an individual (e.g., class speaking, pop quizzes, and fast-paced lectures). Twenty of the items are also separated into three factors: environment (e.g., noisy classrooms), perception (e.g., unclear assignments), and demand (e.g., term papers).

Participants recorded the extent of worry they have on various academic issues, such as studying for examinations, class speaking, pop quizzes, hot classrooms, poor classroom lighting, and final grades. Items were presented with a 1000-point Likert-type scale. Written instructions were presented as follows: If the event is more stressful to you than taking an examination, rate the item between 501 and 1000. If the event is less stressful to you than taking an examination, please rate it between 1 and 499. If it is as stressful as taking an examination, please rate it 500. Responses were summed and averaged to create a total academic worry score. Higher scores indicate more academic worry.

Using Cronbach's alpha, Kohn and Frazer (1986) found internal consistency for all 35 stressors to be 0.92. They also computed reliability for the composite instrument via the split-half method, which produced a coefficient of 0.86. Reliability of each subscale and factor was also assessed by Cronbach's alpha and ranged from 0.73 to 0.84 (Kohn and Frazer 1986). Furthermore, the predictive validity of the Academic Stress Scale has been found to be satisfactory (Burnett and Fanshawe 1996).

Procedure

Four hundred and eighty-three students were systematically selected by selecting every 25thundergraduate student from the front to back of the Student Directory, which lists students in alphabetical order. A systematic sample was generated in order to obtain a representative sample of the population of undergraduate students at Emory University. Due to situational constraints, this method was considered to be the most appropriate approach. Furthermore, the method of selecting every 25th undergraduate student from the Student Directory was thought to more accurately yield uniform coverage of the entire Emory community. This method was not random, but it was more evenly spread over the population, more precise, and easier to draw without mistakes. Also, particular characteristics did not arise in the sampling frame at regular units, thus systematic sampling was a practical approach.

Once a sample was generated, an email was sent to each selected student in order to reach them as quickly as possible. Since the surveys were administered during midterms, we attempted to relate to the students by identifying the survey as a way to alleviate stress and further our understanding of the effect of their academic worry on sleep patterns. The subject line of each email read "Relieve Your Stress". Moreover, in an effort to increase response rate, the top of each email included a color picture of a cartoon character sitting at a desk, with his tongue sticking out and an apprehensive expression on his face. The first line of the email contained large letters in various colors that asked the student: "Stressed out from midterms?" The selected students were then asked to click on a link that directed them to a website that contained the survey (http://www.surveymonkey.com). The initial response rate was 16.6%.

The selected students responded to the questionnaire on a voluntary and anonymous basis. After reading a consent form that described the study as examining the effect of worry in students on their quality of sleep, participants indicated consent by clicking on a button labeled "next." Participants were given a series of questionnaires arranged in the following order: demographics sheet (see Appendix A), SAW (see Appendix B), and Academic Stress Scale (see Appendix C). The demographics sheet requested information about the participants' gender, year in school, and amount of time, in hours and minutes, that they habitually sleep, on average in every 24-hour period. After completing the survey, participants were thanked for their participation.

Results

All variables were examined for normality using the Kolmogrov-Smirnov Test. The test results for sleep length, Z = 1.14, p = 0.15, total SAW scores, Z = 0.92, p = 0.36, and academic worry, Z = 0.80, p = 0.55, were all non-significant thus the assumption of normality was not violated, and parametric statistics were employed in analyses. Furthermore, since the sample contained more females than males, gender differences for sleep length, academic worry, and total SAW scores were explored. No significant gender differences were found for sleep length, t(53) = -0.42, p = 0.16, academic worry, t(53) = 0.35, p = 0.73, or total SAW scores, t(53) = -1.49, p = 0.14. Hence, all responses were combined for subsequent analyses.

Our first hypothesis was that students who have more academic worries will report less sleep than those with less academic worries. The mean habitual sleep length reported was 7.05 hours (SD = 1.11). Worry scores were calculated by taking the average total worry score for each participant. The mean on the Academic Stress Scale was 336.78 (SD = 121.37). In a sample of college students from four Midwestern universities, Kohn and Frazer (1986) identified the mean rating on all 35 items to be 324.50. To determine if our sample differed from Kohn and Frazer's sample, we compared the mean of the current sample to that of the previous sample using a one-sample t-test. No significant differences were found between the two samples, t(54) = 0.75, p = 0.46. This indicates that the amount of academic worry experienced by our sample was consistent with that of the former sample.

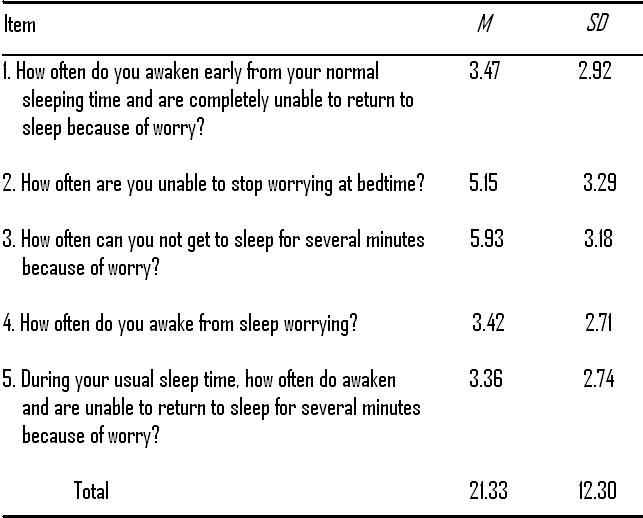

Table 1. Means and standard deviations for SAW items. (n = 55; SAW = Sleep Disturbance Ascribed to Worry Scale).

To assess the relation of academic worry and sleep length, a Pearson correlation was calculated. As predicted, sleep length was significantly negatively related to Academic Stress Scale scores, r = -0.224, p = 0.05. The results indicate a small to moderate effect size, suggesting that the results approach moderate significance.

We further examined the effect of sleep disturbances attributed to worry on sleep length. It was hypothesized that an increase in sleep disturbance ascribed to worry would predict less sleep. Table 1 presents a summary of the means and standard deviations of SAW items and SAW total. A Pearson correlation between the total SAW score and sleep length was calculated. Results supported the prediction that sleep disturbance ascribed to worry will lead to less sleep. Sleep length was significantly negatively related to SAW scores, r = -0.27, p = 0.02, indicating a moderate effect size.

The relationship between SAW scores and scores on the Academic Stress Scale was also evaluated. Since the SAW scale is a measure of sleep disturbance because of worry and the Academic Stress Scale assesses amount of student worry, the two were expected to be positively related. Scores on both scales were significantly moderately related, r = 0.25, p = 0.03.

Subsequent regression analyses were calculated. First, a simple regression was computed to test the relationship between worry and habitual sleep length, using sleep length as the criterion and academic worry scores as the predictor variable. Academic worry scores accounted for 5% of the variance in sleep length, which approached significance, F(1,54) = 2.79, p = 0.10. The effect size was small. The beta weight indicated a negative relationship between academic worry and sleep length (β = -0.22).

Next, a multiple regression was calculated to examine the influence of SAW scores on the relationship between academic worry and sleep length. Sleep length was the criterion variable; SAW and academic worry scores were the predictor variables. In order to account for SAW variance in the relationship between sleep length and worry, SAW scores were entered first into the equation. SAW scores accounted for 7.3% of the variance, which was significant, F(1, 54) = 4.16, p = 0.05. The effect size approached moderate significance. The beta weight indicated a negative relationship between sleep disturbance attributed to worry and sleep length (β = -0.27). When academic worry was entered into the equation, it did not account for any significant additional variance, t = -1.22, p = 0.23, and predictive power from the SAW was lost, t = -1.68, p = 0.10.

Discussion

This study explored the effect of academic worry on sleep quality of college students. Sleep disturbance ascribed to worry and length of sleep were established as indicators of sleep quality. Although McCann and Stewin (1988) and Hartmann et al. (1972) suggested that worry and sleep length were positively related, our results contradict this notion. The findings of this study, however, were consistent with the conclusions of Kelly (2002). They indicate that college students who are characterized by more academic worries sleep less. As predicted, there seems to be a negative relationship between worry and sleep quality.

Also consistent with our prediction, sleep disturbance ascribed to worry was negatively correlated with sleep length. Sleep disturbance resulting from worry thus negatively affects length of sleep. The relationship between sleep disturbance ascribed to worry and sleep length, though, appeared to exist irrespective of academic worry. Hence, academic worry is not the sole contributor to less sleep and does not predict sleep patterns above and beyond sleep disturbance ascribed to worry. Therefore, it is possible that less sleep as a result of worry may be due to factors other than academic worry, such as relationship or financial worry.

It also seems that academic worry and sleep length are negatively correlated irrespective of sleep disturbance ascribed to worry. Sleep disturbance attributed to worry may not be the only factor leading to less sleep in worriers. These relationships among academic worry, sleep disturbance ascribed to worry, and sleep length are present because academic worry attenuated the predictive power of the SAW when entered into the multiple regression model. Since total SAW scores were significantly positively correlated with academic worry scores, overlapping between academic worry and sleep disturbance attributed to worry was probably responsible for this effect.

Nevertheless, college students who tend to worry about academics more often than other college students tend to sleep less. Contradictory to the suggestions of Kelly (2003b), the domain of academic worry has consequential ramifications for sleep quality.

The cognitive activity of worry is thus an important determinant of sleep disturbance in college students. Watts, Coyle, and East (1994) suggest that increased levels of mental activity associated with work-related situations are apparent in individuals suffering from loss of sleep. Cognitive arousal in terms of academic worry seems to hold relevance in determining daily sleep. Increased levels of cognitive activity may act as compensation for the lower levels of cortical arousal exhibited by short sleepers (Kelly 2002). Short sleepers accordingly manifest the cognitive symptom of worrying.

Consider the cognitive arousal of college students. Students who have been told that they would have to present a speech on a given topic when they awoke from their sleep have been shown to need almost twice as long to fall asleep as students who were not told anything (Watts et al. 1994). Furthermore, individuals with sleep disturbances repeatedly complained of higher levels of cognitive intrusions (Watts et al. 1994). The attribution of less sleep to the arousal of academic worry is evident from these results.

But to understand why increased levels of cognitive worry lead to less sleep, we must consider the development of the human brain. The brain provides individuals with the skills necessary to solve context-specific dilemmas that uniquely arise within an environment (Tooby and Cosmides 1990; Pinker 2002). Thus, the brain is resilient when facing decreased levels of cortical activity in short sleepers, attempting to offset this low arousal. Seemingly, short sleepers would exhibit cognitive symptoms to compensate for low cortical levels. Worry, moreover, has been associated with increased levels of cortical activity (Watts et al. 1994; Kelly 2002). Short sleepers, therefore, may demonstrate increases in worry as their brain attempts to return their cortical levels to normal.

Such an abundance of worry present in college life leads us to consider the framework for students' worries. Stark and Traxler (1974) proposed that the amount of worry and anxiety experienced by college students depends upon how well they have resolved identity issues. Identity achievement refers to the process of experimenting, selecting, and integrating self-images; identity diffusion or crisis refers to the inability to establish a direction in life and to commit to an occupational position (Erikson 1968). College is a crucial period in the process of identity formation (Marcia 1966). According to Erikson (1968), identity formation occurs throughout adolescence, but college represents a critical time in which the identity process either crystallizes or diffuses. The college atmosphere presents students with continuous opportunities to evaluate themselves in an array of activities without making premature commitments. But as individuals progress through college, they are expected to have a more integrated identity (Arehart and Smith 1990). Nevertheless, life contexts such as the college environment, along with academic and social demands, make the process of identity attainment difficult (Arehart and Smith 1990). Hence, the search for identity causes an individual to encounter worrisome circumstances.

College students are typically characterized as holding an identity status of foreclosure, meaning they are committed to goals and values, yet have not gone through a reflective process of personal exploration (Marcia 1966; Whitbourne and Tesch 1985). Unsuccessful resolution of these identity issues occur when individuals exhibit worrisome views of experience (Arehart and Smith 1990). The growth of cognitive abilities to control negative appraisals, however, usually occurs as life in college progresses, stimulating identity resolution and development (Erikson 1968).

Accordingly, the consolidation of an identity is associated with amount of worry. Stark and Traxler (1974) have indicated a negative relationship between identity formation and worry, stating that college students who are low on identity diffusion are relatively worry-free. Worry and identity attainment are consequently related to sleep disturbance (Wagner, Lorion, and Shipley 1983).

Wagner et al. (1983) contend that stressors that reduce sleep in college students arise from school pressures, the presence of psychological conflicts, and identity resolution. The ability to resolve conflicts and deal with worry agents thus coincides with an individual's adjustment to the process of identity formation. Therefore, sleep disturbances are displayed by those college students who have less effectively resolved the identity crisis (Wagner et al. 1983). Identity disturbed students are further associated with high worry and anxiety levels (Wagner et al. 1983). Consequently, identity attainment may contribute to the reduction of worry, and thus may increase in sleep length.

This research has suggested that academic worry has a significant effect on sleep length in a college population. It adds to the growing research on worry as a separate construct from anxiety. It further illustrates that specific domains of worry, particularly academic worry, can have consequential effects on sleep behavior. Explanations for sleep disturbances, however, are certainly not limited to sleep disturbance ascribed to worry and academic worry. Additional variables may be involved in determining sleep length, especially since SAW scores and academic worry scores accounted for a low percentage of variance. Psychologists need to assess other factors that combine with worry to predict sleep. It should also be evaluated whether these results would remain constant across other domains of worry.

Differences in sleep length between worriers and non-worriers may have been so pronounced due to the conditions under which the study was conducted. During data collection, students were involved in preparing for many midterm examinations. Since frequency of test taking was probably higher than normal, our sample might have been experiencing more worry and less sleep than usual. There may have been a restriction of range since everyone could have been sleeping less. Even though the worry scale assessed general, everyday stressors, the SAW scale evaluated usual sleep patterns, and sleep was measured as habitual length, responses may still have been influenced. It may be difficult to confirm that the results were representative of college students that are under less pressure. Future research should focus on a more long-term study of the relationship between worry and sleep, making sure to evaluate students under situations that yield varying degrees of worry.

In conducting future studies, researchers should attempt to increase the response rate and thus increase statistical power. Questionnaires should be distributed in person, rather than by email. With this approach, individuals may feel more inclined to participate.

Other limitations are also present in this current approach that should be considered for future research. In addition to the single-item measure of sleep length, sleep diaries could also be considered as a measure of sleep length because studies need to go beyond the use of questionnaires. It may be more valuable to obtain reports about the thought content of individuals experiencing sleep disturbance to examine the focus of worry. Hence, the content of students' thoughts should be evaluated while they are lying in bed unable to sleep, or during the time leading up to when they go to sleep. This could be achieved by asking individuals in a sleep lab to record their thoughts.

It was concluded that academic worry and sleep disturbance ascribed to worry were both negatively correlated with sleep length. Support for additional examination of worry as a determinant of sleep length is provided by our results. The findings cannot be interpreted as evidence of a causal link between academic worry and sleep length since the study was correlational in nature. That link, however, can be established through further longitudinal research. Nevertheless, worry certainly affects the sleep of college students in an environment exemplified by constant pressures and identity formation.

Acknowledgments

The author wishes to express his appreciation to Deborah Kozy for her assistance with the research, and Mark Gapen, B.A. for his help and support with this study.

References

Arehart, D.M. and P.H. Smith. (1990) Identity in adolescence: Influences of dysfunction and psychosocial task issues. Journal of Youth and Adolescence 19(1), 63-72.

Burnett, P.C. and J.P. Fanshawe. (1997) Measuring school-related stressors in adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence 26(4), 415-428.

Erikson, E.H. (1968) Identity: Youth and crisis. New York: Norton.

Frazer, G.H. and J.P. Kohn. (1986) An academic stress scale: Identification and rated importance of academic stressors. Psychological Reports 59(2), 415-426.

Gana, K., Martin, B., and M. Canouet. (2001) Worry and anxiety: Is there a causal relationship? Psychopathology 34(5), 221-229.

Hartmann, E., Baekeland, F., and G.R. Zwilling. (1972) Psychological differences between long and short sleepers. Archives of General Psychiatry 26, 463-468.

Hicks, R.A. and E.R. Garcia. (1987) Level of stress and sleep duration. Perceptual and Motor Skills 64(1), 44-46.

Hicks, R.A. and R.J. Pellegrini. (1977) Anxiety levels of short and long sleepers. Psychological Reports 41(2), 569-570.

Hicks, R.A., Pellegrini, R.J., and J. Hawkins. (1979) Test anxiety levels of short and long sleeping college students. Psychological Reports 44(3), 712-714.

Kelly, W.E. (2002) Worry and sleep length revisited: Worry, sleep length, and sleep disturbance ascribed to worry. The Journal of Genetic Psychology 163(3), 296-304.

Kelly, W.E. (2003a) Some correlates sleep disturbance ascribed to worry. Individual Differences Research 1(2), 137-146.

Kelly, W.E. (2003b) Worry content associated with decreased sleep-length among college students. College Student Journal 37(1), 93-95.

Kelly, W.E. and A. Forbes. (2004) Temporal stability of the Sleep Disturbance Ascribed to Worry Scale. Perceptual and Motor Skills 99(2), 628.

Kumar, A. and A.K. Vaidya. (1984) Anxiety as a personality dimension of short and long sleepers. Journal of Clinical Psychology 40(1), 197-198.

Marcia, J.E. (1966) Development and validation of ego-identity status. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 3(5), 551-558.

McCann, S.J.H. and L.L. Stewin. (1988) Worry, anxiety, and preferred length of sleep. Journal of Genetic Psychology 149(3), 413-418.

Muss, R.E. (1996) Theories of adolescence: Sixth edition. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Pinker, S. (2002) The Blank Slate: The Modern Denial of Human Nature. New York: Viking Penguin.

Stark, P.A. and A.J. Traxler. (1974) Empirical validation of Erikson's theory of identity crisis in late adolescence. Journal of Psychology: Interdisciplinary & Applied 86(1), 25-33.

Tooby, J. and L. Cosmides (1990) On the universality of human nature and the uniqueness of the individual: The role of genetics and adaptation. Journal of Personality 58, 17-67.

Verlander, L.A, Benedict, J.O., and D.P. Hanson. (1999) Stress and sleep patterns of college students. Perceptual and Motor Skills 88(3), 893-898.

Wagner, K.D., Lorion, R.P., and T.E. Shipley. (1983) Insomnia and psychosocial crisis: Two studies of Erikson's developmental theory. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology51(4), 595-603.

Watts, F.N., Coyle, K., and M.P. East. (1994) The contribution of worry to insomnia. British Journal of Clinical Psychology 33(2), 211-220.

Whitbourne, S.K. and S.A Tesch. (1985) A comparison of identity and intimacy statuses in college students and alumni. Developmental Psychology 21(6), 1039-1044.